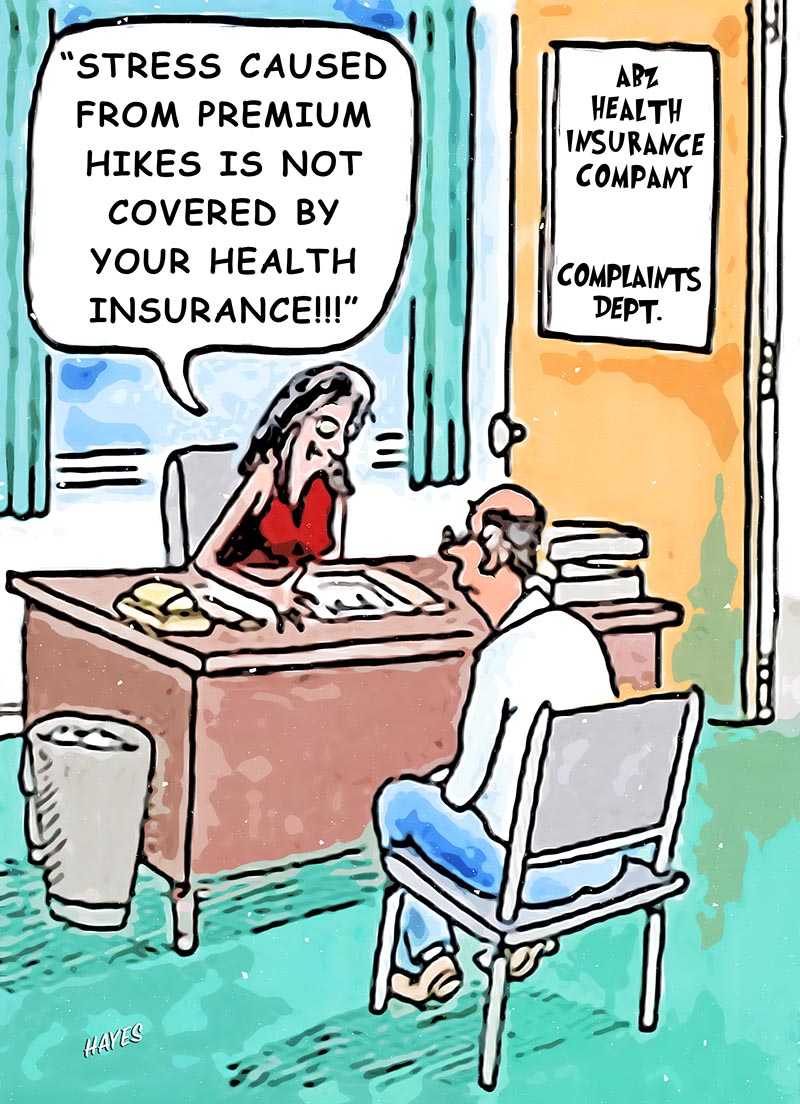

Health care is not equal

Last week the Grapevine lifted the lid on the inequity of Medicare and the profiteering associated with the ever increasing costs of private health insurance. So, why are insurance premiums so high?

13 March 2024

ALAN HAYES

AS private health insurance companies get ready to tap millions of Australians for more money, consumers are left wondering what happened to affordable and equitable health insurance for everyone? You can blame successive governments who have allowed twenty years of mergers, where the only guaranteed outcome is shareholder profits. And if you think you have a choice in insurance by shopping around, think again! Because you are wrong! Thanks to market concentration, all you've got left is an illusion that you can shop around.

When Health Minister Mark Butler dropped the bombshell, last week he said, “I wasn’t prepared to just tick and flick the claims of health insurers, as the Opposition was urging me to do. I asked insurers to go back and sharpen their pencils and put forward a more reasonable offer for the 15 million Australians with private health insurance.

“The Government has approved an average industry premium increase of just 3.03 per cent.”

So, it was little wonder that last Friday, when my health insurer sent me the expected but dreaded email that they wouldn’t be tardy about a price increase in my monthly premium it was with some trepidation I read the expected news – to be polite I’ll say my jaw dropped and bounce on the floor several times. Five per cent increase - not 3.03 per cent as our health minister had said, but an extra two percent. Of course, there was the usual rhetoric about how expensive it was for them to run a business – “As much as we’d love to keep things on hold, the costs of healthcare are rising in Australia,” they said.

My heart strings tighten with contempt, but certainly not for sympathy – I was reminded that the rewards benefit I received from this mutual fund was closing and that I should hurry up and redeem my remaining rewards for eligible out-of-pocket medical expenses. Glory be! I was entitled to claim $86.97 if I made sure I was sick or had an accident before 30 October 2024 – after then the mutual benefit was no longer mutual.

What can consumers do, who likewise are experiencing the health premium shock? As I’ve already said, shopping around is futile but I decided to check out how much other health insurers were raising their premiums.

On average, most had opted for around 4 per cent; some were less, even below 3 per cent and there was two that had a zero per cent increase. So, I thought this sounds too good to be true and maybe not every insurer is keen to drive consumers into penury.

The premium increase of those insurers prior to the increase and who were below 3 percent and zero, was so expensive that you wouldn’t want to insure with them!

Not surprisingly, there’s been a lot of criticism, despite Health Minister Mark Butler claiming that he’d insisted on health insurers sharpening their pencils - it would seem that the health minister’s pleas fell on many a deaf ear.

The first health insurer to be slated in the mainstream media was NIB Health Funds Ltd for jacking up their premiums by 4.1 per cent on some policies by more than the approved rate, the same day the minister’s announcement was made.

However, NIB's CEO and managing director Mark Fitzgibbon defended their position and said the increase reflects the rise in health and medical treatment costs post-COVID.

"We’re doing our very best to maintain affordability yet spending is growing across healthcare, driven by an ageing population, the rise of chronic conditions and the cost of new technologies," he said in an ASX announcement.

Despite Mr Fitzgibbon’s claims, NIB is a shareholder owned company that operates in all states and territories on a for-profit basis.

There is no doubt that NIB is there for the benefit of shareholders as, just like the many years of health fund mergers, policies are re sold under a number of different brands, including:

- AAMI Health Insurance

- Apia Health Insurance

- ING Health Insurance

- Priceline Health Insurance

- Qantas Insurance

- Real Health Insurance

- Seniors Health Insurance

- Suncorp Health Insurance

The corporatisation of Health insurers has seen huge profits through the ownership of hospitals and medical centres and from becoming corporate giants. BUPA, which swallowed up the Medical Benefits Fund (MBF), has its global headquarters in the United Kingdom. Its main countries of operation are Australia, Spain, the United Kingdom, Chile, Poland, New Zealand, Hong Kong, Turkey, Brazil, Ireland, Mexico and the United States. It also has a presence across Latin America, the Middle East and Asia, including joint ventures in Saudi Arabia and India.

Bupa runs various health provision services for a further 19.2 million customers worldwide, including hospitals, outpatient clinics, dental centres and digital services. Bupa also runs aged care facilities in four countries; the United Kingdom, Australia, Spain and New Zealand.

And what about Medibank? Originally established by the Australian Government as a not-for-profit health fund by the Whitlam Government in 1975. In May 2009, the Rudd government announced that Medibank would become a "for profit" business and would pay tax on its earnings. The process of converting the status of the business was completed on 1 October 2009 following approval from the then regulator, the Private Health Insurance Administration Council (PHIAC). In the same year Medibank bought Wollongong-based health insurer AHM.

The list of health insurers acquiring other health insurance companies goes on but regardless, they are there for the money, not for some altruistic reason.

So, the 1 April price hike in health insurance premiums may have been good news for the health insurance companies but is a ‘kick-in-the-guts’ for those struggling to afford it. It is the largest increase in three years, yet Minister for Health Mark Butler still maintains that it remains below those of wages and inflation, which increased by 4.2 per cent and 4.1 per cent, respectively, in 2023.

The increase in 2024 is slightly higher than the rise of 2.9 per cent in 2023 and 2.7 per cent in 2022 and 2021.

Extrapolating the 6% from 2021 to the Australian population, this represents approximately 1.5 million Australians who do not have enough money to pay for needed health care – this will only get worse.

And what about our alleged ‘universal’ health coverage, Medicare?

According to the World Health Organization, universal health coverage means equitable access to high quality care when it is needed and without causing financial stress for patients and their families.

Analyses published over several years by the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) shows that Australia has higher than the OECD average out-of-pocket health costs and this has been raised for several years in other reports.

For example, variation in private specialists’ fees in Australia has been an ongoing debate. There appears to be no sound evidence or rationale for the variation, and no data linking higher quality of care with higher fees. Despite practical and implementable solutions being proposed, such as covering the cost of diagnostic services and funding telehealth joint consults between GPs and specialists to reduce referrals, there is yet to be a comprehensive strategic response from government to reduce out-of-pocket health care costs.

In Australia, 15% of all expenditure on health care comes directly from individuals in the form of out‐of‐pocket fees — this is almost double the amount contributed by private health insurers. There is concern that vulnerable groups — socio‐economically disadvantaged people and older Australians in particular, who also have higher health care needs — are spending larger proportions of their incomes on out‐of‐pocket fees for health care.

Yet despite all the promises, and the government’s claim that their tax cuts on 1 July will mean that all Australian taxpayers will earn more and keep more of what they earn, you cannot help but being cynical. Because what Australian’s save in tax cuts will more than likely subsidise the rising cost of their health insurance – if they can afford it.

It won’t be long before our health system has plummeted into the American model – only those with money will be able to afford it.

.jpg?crc=4257584689)

_web.jpg?crc=282450513)